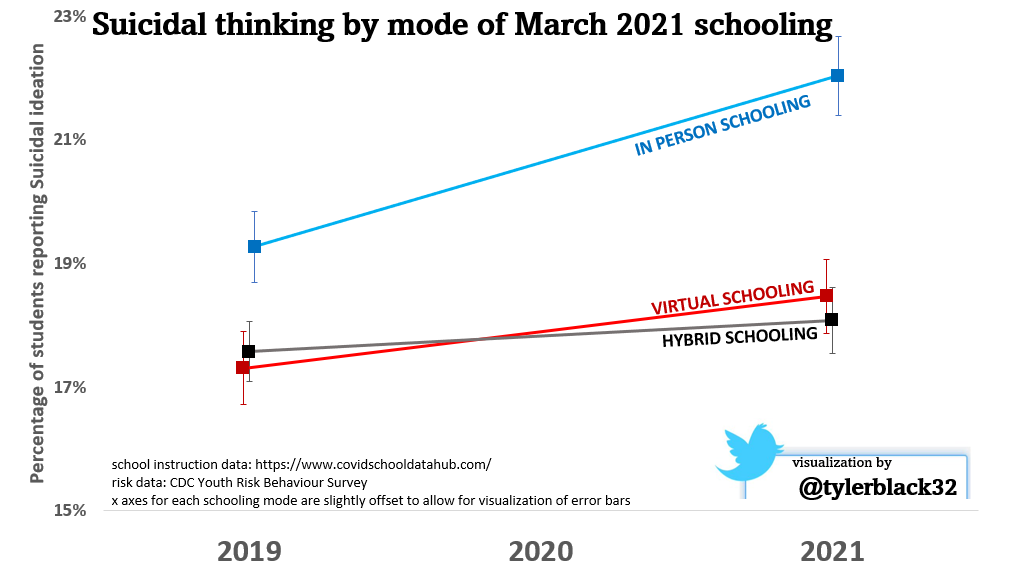

Quick Report: Suicidal thinking showed larger increases in "in-person" instruction districts than in "virtual" or "hybrid" instruction districts

Moral panic: school closures caused suicidal thinking. The Evidence: in-person schooling was associated with increases in suicidal thinking.

Many articles, experts, and politicians have blamed the mental health crisis on school closures during the coronavirus pandemic. We now have high quality data from the CDC Youth Behavior Risk Survey. As promised in a previous post about this survey, I’m taking a closer look at the CDC’s data, and staying on focus with the “Seriously Considered Attempting Suicide” question. For this quick analysis, I downloaded the city level-data that was available, and coded each cities according to the March 2021 “schooling status” — most YBRS surveys are done in the spring semester of 2021 or later.

So, we can actually ask this central question. For cities that were virtual schooling, did suicidal thinking get worse? What about for cities that were in-person schooling? Was there a difference between them?

Brief Research: Suicidal Thinking Changes by mode of school instruction in a study of 52,133 American high school students

By Tyler R. Black

Author affiliations: University of British Columbia, Department of Psychiatry

Method:

The CDC YBRSS data of American high school students was extracted for the “seriously considered attempting suicide” question for 26 cities representing 52,133 students (in 2021). The rates of reporting suicidal ideation between 2021 and 2019 were compared using the odds ratios, and all calculations were done in Microsoft Excel. Coding for schooling type was done in two levels: a binary “in person” vs “not in person”, and a ternary “in person” vs “not in person” vs “hybrid”. The website “Covidschooldata.org” was used and dates were set to March 2021 for each state. State level .CSV files were downloaded and constructions of the city’s districts were made by searching for each district within each city and selecting the code based upon predominance by enrollment, and if enrollment data wasn’t included, by number of districts.

Results

Overall response rates for the item “Seriously Considered Attempting Suicide in the past 12 months” are shown in Figure 1.

Odds ratios for “seriously considered attempting suicide” rate in 2021 compared to 2019 are shown in Figure 2. For high-school youth completing the YBRSS in spring of 2021 compared to spring 2019, the odds ratio for suicidal ideation was higher in the in-person group (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.12-1.25), higher in the virtual group (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02-1.15), and unchanged in the hybrid group (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.99-1.05). When “not-in-person” coding was grouped, there was a small increase in 2021 suicidal thinking (OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.02 - 1.10).

Blog-style Discussion

Though correlations like these are never causative, if the hypothesis is that “suicidal thinking increased more in cities that were ‘virtual schooling’ through spring of 2021”, this hypothesis is rejected in analysis. Similarly, if our hypothesis was that “getting back to school by spring of 2021 was associated with better outcomes in 2021 suicidal thinking”, we must also reject that hypothesis.

Personally, I believe that the addition of returning to school in the midst of a global pandemic that was killing hundreds of thousands of Americans may have increased distress in the survey-takers. This data would be what we would see if that hypothesis was true (though it certainly does not in itself establish any of it) - children who were used to virtual and hybrid instruction did not have the added pressure of returning to in-person classes, and may have benefited.

Limitations

Though the strength of this analysis lies in the city-level mapping, there are some significant limitations. First, the city-level “March 2021 schooling mode” sometimes had to be approximated by population of district and visual approximation, a source of potential error. Second, the “March 2021 school mode” was not randomly controlled and thus this is a population-level cohort study; unfortunately, this means that there are many confounding variables that could account for the differences within the state including even basic demographic variables. Third, even within the cities this is not longitudinal data, so within-city confounding variables introduce a likely source of error.

Conclusion of the Research

According to CDC city-level data of over 50,000 students, attending full-time in-person instruction in March of 2021 was associated with greater increases in the proportion of students with suicidal thinking within that district than those who did not attend full-time in-person instruction. Both virtual and in-person schooling in March 2021 were associated with increases in suicidal thinking.

This data does not support the widely-held belief that in-person schooling was associated with reductions in suicidal thinking. It is important that data drive our statements and opinions on mental health outcomes of pandemic-related school changes.

Sources:

CDC YBRS data: https://nccd.cdc.gov/Youthonline/App/Default.aspx

School-district data: https://www.covidschooldatahub.com

Sources of Funding, Financial Conflicts of Interest:

The author reports no financial conflicts of interest.

Hey! Consider subscribing! It would really help me feel like my work here is worthwhile.